How to Fly a Plane

“Flying a plane is no different from riding a bicycle; it’s just a lot harder to put baseball cards in the spokes.” – Capt. Rex Kramer (“Airplane!,” 1980)

Saturday, June 7, 2025

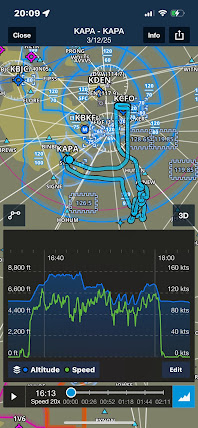

Final Stage Check (redux)

Lesson (well, it's been a while)

Wow, have I left this iron unattended for a long time. So, an update is in order.

In February of 2024, my instructor signed me off for my final stage check. This was it. I needed to pass this in order to get the endorsement for my check ride. I was ready. I knew what I was doing. Nothing could stop me!

Oooooorrrrrrrrrr so I thought.

After a reschedule or two due to weather, my evaluating instructor had a 7AM time slot available for this check ride. Did I mention I'm not a morning person? Nonetheless, I was confident. I had this in the bag! Take off went well. We started on the cross country portion of the check ride. My instructor asked me to tune in a VOR (navigation) frequency. My mind went blank. Poof. Nothing. He may as well had asked me to recite "Hamlet" in the original Klingon. I knew there was a way to do it, but, nothing. He pointed out the simple button that I had completely forgot. Duh. I tuned things in and we proceeded, but that was pretty much indicative of how the rest of the flight would go. My mind simply was not in the game, one thing compounded the next. We flew a bit. None of it pretty. We went to do stalls. U-G-L-Y, and I didn't have an alibi. When you almost put the plane into a spin on your first stall, that puts a pretty quick end to the stage check. He asked if I wanted to continue and I said yes. I figured I'd at least get past the rest of the requisite maneuvers if for no other reason than to get an appraisal of how bad I had jacked things up.

We landed. We debriefed. It really wasn't as bad as I had thought it was, but it was definitely NOT up to snuff for being signed off for a final check ride with an FAA examiner. I couldn't argue. My evaluating instructor was spot on. Tough, but not at all wrong. It was not a good day for me. Was it just a bad day? Or was it something more? We agreed that a few more flights with my instructor to tweak things, and we'd try again in a month or so.

Did I mention Spring in the Rockies is a miserable time to try to fly? I got up solo a few weeks later, but then it was maybe once a month until late Summer that I got to flying with any regularity. What followed was 6 months of flying every other week or so, sometimes doing pattern work, sometimes heading out to the practice area to work on maneuvers. Every time, just a little more confidence. I felt like a kid asking "are we there yet?" with my instructor on whether he thought I was ready to have another go at the stage check. At times I was beside myself frustrated because I felt ready. For whatever reason, he was reluctant. I never asked why. I just took it as a challenge to do better the next time.

Finally, around September or October of 2024, my instructor said I was solid and ready to have another go at things. I couldn't have agreed more. The hitch, the evaluating instructor I had flown with in February was now part time, so I would have to wait for his availability. We originally picked a date in the end of November, but weather would cancel this. So I flew with my CFI ever few weeks to keep skills sharp until we could finally get a chance to fly my final stage check again.

Lesson 74 - Long Cross Country (redux again)

If at first you don't succeed... Okay, technically speaking, this was our 4th attempt at flying my long cross country route to Pueblo. The first attempt was cancelled due to maintenance on the plane. The second attempt was thwarted by hot weather and an underperforming airplane. The morning of our third attempt, my instructor calls me saying he was sick as a dog and nearly vomited in the cockpit during his morning flight. I'm not a huge fan of flying in a vomit-filled airplane, so we both thought it best to reschedule. So we did. Six o'clock the following morning.

I am not a morning person. I can function well enough to let the dogs out and maybe get the kids to school, but please don't ask me to do anything complex. Like fly an airplane. And my daughter was going to join us as well, and she is not a morning person, either. Unless she is, which randomly happens when she decides she wants to watch the sun rise. (I assure you, she is my kid, but I don't know where that comes from.) However, I'm trying to push through this process as quickly as possible right now, and I need to get this flight out of the way sooner rather than later. So we agreed to meet at 6 the following morning.

Adrenaline and energy drinks do wonders. I was surprisingly alert when we arrived at the airport. The sun was just thinking about peeking over the horizon, and the weather looked beautiful. My daughter and I met with my instructor, we looked at the weather, talked about the flight, and everything looked good. We got out to the plane, prepped it, pulled it out, and by 7 am, we were airborne. Cooler temperatures and a plane known for its superior climb performance made a world of difference compared to our previous attempt. This was my first time in this plane, and it handled remarkably well.

I was in my element on this flight. Things were just clicking. The skies were smooth, ATC along the way was not at all busy so it was easy to get calls in. We first flew to Colorado Springs. My in-laws live there, just north of the airport, so it was fun to point out their neighborhood to my daughter as we flew over. Landing at the Springs was pretty textbook. Unbeknownst to me, my daughter took video of my landing, so I'm glad it was smooth. we just did a touch-and-go in the Springs, then headed south to Pueblo.

This was my first time flying down to Pueblo. While I had visual landmarks picked out for the trip down, ATC had me fly east, taking me away from the intestate which was to be my reference. So much for that, but Pueblo isn't that far from the Springs, and by the time ATC directed us to turn south, we could pretty much see the general area where the field is. I just scratched my visual waypoints off the list and pretty much flew direct to the airport. If we were to have more time available, we would have stopped and gotten food in Pueblo, but I had to be at work at 10, so we just landed, taxied back, and took off again.

Here again, my landmarks for leaving Pueblo were behind me on our departure, so I scratched off the first waypoint and redid our course to match our departure. Once we passed over Colorado Spring East, which is a small airport not surprisingly east of Colorado Springs, we were pretty much home free. I was thinking about pulling out my foggles and doing some instrument work, but I just wasn't feeling it. I wanted to enjoy the flight. As I was contemplating that, my instructor suggested that he teach me how to use the autopilot. Well, yeah. I can do that. I had flown with a more basic autopilot in an older plane a few flights previous, and this one was a definite improvement. It holds airspeed and altitude in a way that doesn't roll in a bunch of trim and unwittingly slow you to nearly stalling. We flew with the autopilot engaged for nearly 25 minutes, just sitting back, taking in the sights, and really doing not much more than remembering why I torture myself. When we reached Castle Rock, we shut off the autopilot, contacted Centennial, and came home.

All in all, this flight was everything I had hoped it to be. I was confident in every phase of flight. My landings were solid. Not perfect, but solid. My instructor saw that I had a good command of the entire process, and I was able to give my daughter a good introduction to flying. We simply had a grand time. It will be fun to fly this again by myself once I get past my stage check (again), which is now the singular focus of my next few lessons.

Sunday, September 17, 2023

Lesson 69 - Back in the Saddle Again (Again)

It's been a while. Three months to the day, to be exact. This delay wasn't my idea. But aviation is filled unplanned delays. After my stage check, the plan was for me to get back with either of my two instructors, hammer out the short and soft field landings, retest those, and be well on my way to finishing this process. That was the plan. I had things scheduled. Then a hail storm came through and grounded the three Grummans I have been training in. The Cessnas and Pipers were unscathed, but my poor Grummans use a thinner gauge aluminum, and just (literally) got hammered. That cancelled my "brush up my landings" flights.

While I'm waiting for the school to determine if the Grummans are to return to service, both of my instructors left the school. I knew my first instructor was on borrowed time. He had his hours and was just waiting for his class to open up with the regional airline. My second instructor abruptly retired. I was left with no airplanes to fly and no instructors to fly them with.

It took a full three months for that dust to settle. The school had to hire new instructors to pick up the extra students, and I was holding out for an instructor who was comfortable flying the school's Pipers, since they are also low wing, similar to the Grummans. The pieces finally came together again, and three months to the day since my last flight, I'm back in the air. New instructor, new plane, renewed push to get this process finished up!

This flight was a textbook "get to know each other" flight. My instructor and I had never flown together before, and I had never flown the Piper before. (Technically, I flew my friend's Piper, but that was over 20 years ago.) we kept things simple. We flew out to Spaceport, did some touch-and-goes, then returned back to Centennial. That would give my new instructor a solid baseline to gauge where I was and where I needed to go. I felt comfortable in the new plane, and I will say two things. First, where has electric trim been all my life? A simple thumb switch on the yoke allows me to effortlessly set the trim on the plane where it needs to be for climb, cruise, and landing. Second, the Piper is a joy to land for one primary reason. The landing gear built on what amounts to shock absorbers as opposed to long arms of spring metal. The difference is that when the Piper touches down, it has much less tendency to bounce back up. It still can (and does) but with nowhere near the ferocity that the Cessnas and Grummans do. It's much easier to recover from a bounced landing.

The plan going forward? Nail the landings. Get them polished so they would pass a final check ride. Get everything polished to that level, retest the cross country stage check, get that time checked off, then get ready for my final check ride, which should be very easy since my instructor is holding me to those standards at this stage. We have clear-cut expectations and a plan to get there. Now, let's just get this done!

Friday, August 25, 2023

Lesson 73 - External Pressures and Density Altitude

Aviation is full of acronyms. ATOMATOFLAMES, NWKRAFT, IMSAFE, FLAPS, CGUMPS ... It's pretty endless. If you're a pilot and you're reading this, then you know. If you're not, don't sweat it. Just be glad your pilot does when they're in the cockpit. One of the safety acronyms we use is PAVE

Pilot

Airplane

enVironment

External pressure

It's kind of a "go, no-go" checklist that pilots should run through to determine if they should fly the plane. Is the pilot in good shape? Is the plane airworthy? What's the weather? Are there any external pressures which might make you want to fly when it's otherwise not safe to do so? Today's lesson targeted the last two in this checklist.

Today's flight was to be a long cross country flight to Colorado Springs and Pueblo with my instructor in preparation for my eventual solo long cross country flight. Since I have switched from the Grummans to the Pipers, I've had the added benefit of a rear seat in the airplane. Both of my kids have expressed interest in flying with me pretty much since I started this madness over two years ago. While the Cessna 172s I started training in had 4 seats, I was reluctant to fly with my kids because I wasn't comfortable flying. Then I switched to the Grummans, in which I got comfortable enough to carry passengers, except that the Grummans I was flying only had two seats, so with my instructor in the right seat, there was no room for anyone else. I can't carry non-pilot passengers until I get my license. The Grummans got totaled in a hailstorm, so I switched to flying the Piper Archers. Now I have rear seats, willing passengers, and a CFI who says "sure!"

My daughter is fast to play the "eldest child" card whenever possible, so she claimed dibs on the first flight. I wanted it to be something cool, not just flying in the pattern, so I scheduled this long cross country to Pueblo so she could fly with us. She was understandably excited, and I was anxious to make this as memorable of an experience as possible. I figured we'd fly to Colorado Springs, where we'd fly over her grandparents' and her aunt's houses. (They live on the approach to the airport.) Then we'd fly to Pueblo where we'd stop and get some ice cream, then return back to Centennial. It would be a full flight, but a fun one. My desire to fly this for my daughter is a textbook example of an "External pressure" to make the flight.

My instructor had me run a weight-and-balance sheet for the flight since we were carrying an extra passenger. This is a sheet where we total up the weight of everything on the plane, and based on that weight, the outside temperature and atmospheric pressure, and published performance data for the airplane, determine if it's safe to fly, and what kind of performance we can expect. This is the "enVironment" part of the acronym. I ran the numbers, and based on published charts, we were under the maximum allowable weight even with full fuel tanks, and performance would be on par with other flights despite temperatures expected to be a bit on the warm side. Things looked good. On paper.

We arrived at the field, and I got the plane ready while my daughter gleefully snapped countless photos on her phone of the process. My instructor looked over my weight-and-balance sheet and agreed that we were in good shape based on the published data. We loaded everybody and everything up and set out on our journey. I taxied us to the run-up area where things were textbook. I had the flight plan pulled up on my iPad to get us down to the Springs. ATC cleared us to take off on runway 10, which was going to save us a good bit of time in its own right. We decided to try a short field take-off since I'm working on perfecting those techniques. The temperature was around 80 degrees, and the density altitude at the airport was reported at 8,900'. (Density Altitude is the altitude that the plane feels like it's flying at. Warm air is less dense, and higher elevations have less dense air, so the warmer it is, the higher it "feels" to objects flying through them. A density altitude of 8,900' is high, but not unusual for Summer. Plenty of small planes were flying today, and besides, things looked good. On paper.

Lined up on the runway, brakes set, 25 degrees of flaps, full throttle, release brakes, and we're off. The plane seemed a bit lethargic compared to what I was used to, but we're also carrying an extra body and full fuel. We're still below max gross weight, though. We're good. I reach 64 knots and begin to pull the nose back to take off. We take off. Almost immediately, the stall horn sounds. I pitch the nose down to level flight to try to gain more airspeed. Not really gaining much speed. Maybe a little, but I'm also not climbing. I pitch up a bit to try to gain altitude, and the stall horn starts chirping again. Level off, gain a bit of speed, pitch up to climb again, and the stall horn sounds again.

This is only my 5th time flying the Piper Archer, and my third in this specific airplane. I have not had a chance to really get a feel for how these planes perform to know if it's performance--or lack thereof--is operator error or something else. But I was beginning to take this personally that this plane simply did not want to listen to my command to climb. Stall horn. Level off to gain airspeed, climb, stall horn again. At this point, my instructor senses something not right (operator error or ?) and takes the controls. I'm thinking he's going to do some magic experienced pilot stuff and get us on an even keel, and I can debrief with him later what I was doing wrong. Nope. Stall horn, level off, gain a little air speed, try to climb again, lather, rinse, repeat. We had made it to Parker, which by this time we should have been at 7,500' We were barely at 7,000'. This was not good. At least I was comfortable knowing it wasn't operator error, but that still didn't change the fact that this plane was just not gaining altitude near fast enough to suit our tastes. We contemplated turning back, but weren't quite ready to call it a day. After all, this was supposed to be the fun long cross country flight with my daughter that she would remember forever. (She was oblivious to any difficulties we were having in the front row of seats, continuing her enthusiastic documentation of every minute of the flight on Instagram to rub it into her friends.)

We finally got enough airspeed to where we could climb without the stall horn chirping, but we were not climbing very quickly at all. My instructor checked the density altitude for Colorado Springs. They had a density altitude of 9,200'. Ugh. Not good. If we were getting this poor performance here, we'd likely get even worse performance there. Decision time. The enVironment was turning against us. We weren't losing altitude, so immediate safety wasn't an issue. There were External pressures to continue the flight. My daughter deserved to have a fun, full flight.

I'll be honest in saying I was solidly on the fence at first. I said "let's give it a minute" to see if things calmed down. Again, we weren't losing altitude, so an extra minute to see if things changed wasn't that much of a risk. The stall horn chirping while we were only 500' above the ground was unnerving, but as we gained altitude and began to quiet the stall horn, there was a moment when I thought maybe things were changing.

Things didn't change. I could sense my instructor was just a bit uncomfortable. This wasn't a "what do you think?" kind of situation where he's asking because he could go either way and wants to know my thoughts. He was genuinely concerned. That was enough for me. That's it, we're landing. Not worth the risk. Live to fly another day. We told ATC we were returning to the airport. They cleared us to land on the runway we just took off from. I made an uneventful approach and despite flaring just a bit too early (now the plane wants to fly!) sat down safely and just a little bit past where I was hoping to. We taxied back to the ramp, tied down, took a few more pictures, and headed in to try to figure out why there was such a discrepancy between what was on paper and what we experienced.

We pulled up the performance charts, and "on paper," we should have had been able to achieve a climb rate near 350 feet per minute. In the 10 minutes from when our wheels left the ground to when we decided to land, we gained only 1,680' in elevation. That's 168 feet per minute, about half of what we were expecting. It's important to note that the "service ceiling" for any aircraft is the altitude at which its climb rate falls below 100 feet per minute. We weren't too far above that at all. Suffice to say even if we were to continue the flight, I would have spent the time worrying about the poor performance, not concentrating on flying the route.

Factors? First, there's obviously the weather. Planes don't perform well at high density altitudes, and performance charts may not mirror real world conditions. How much that is off is hard to measure; it's just something you have to feel in the air. Second, there's the age of the plane. Compared to some I've flown, this plane is a relative Spring chicken. But age still plays a factor. What we think played a large part is the spinny thing at the front of the plane.

Like any mechanical device, you can get speed or power, but getting both at the same time is a rare treat. Airplane propellers work by creating thrust as the blades spin around. Depending on the pitch of the propeller, you can get good speed or good power. Complex airplanes have variable pitch propellers, which allow the pilot to set the pitch of the propellers depending on need. The trainers don't have that feature. A propeller can either be weighted towards good climbing performance--a climbing propeller, or good cruise performance--a cruise propeller. Our plane today was fitted with a cruise propeller. Because of that, its performance on climbs will be less than what's in the manual. This wasn't something I really thought about. I had flown another Archer with a cruise propeller a few lessons back, but didn't notice any real performance issues with it. But, it was a newer plane and we were carrying less weight on that flight. Discussions with other instructors after we landed revealed this plane is known to be a poor performer in hot weather. Now we know.

Friday, August 18, 2023

Lesson 61 - One of THOSE Days

Today's task, a flight out to Limon, CO using GPS and VOR navigation in addition to visual landmarks. This was going to be an easy day. My last flight was my "long cross country," which I had flown with my second instructor, so I was pretty confident in that part of things. Today was going to work more on electronic navigation, using GPS and VOR navigational aids. The weather was cold, and we had just had a fresh snowfall, but other than that, a regular walk in the park.

Yeah, right. I wouldn't have written that if it were true.

This was my first flight with my original CFI after a long time flying with my second CFI. This was mostly just due to scheduling, as I tried to alternate between the two so to balance both styles. I found I'd learn things with one, but be able to better practice them with the other. Weird dynamic, but it got me through my landing difficulties and onto my solo flight, so--hey--whatever works.

Anyway, the first hint today was going to be strange was when I got to the airport and there was a note attached to the book for the plane. "Engine break-in period." The plane had just received a new engine. This meant that we were to fly the plane with the throttle at 100% for every stage of the flight except landings. That also meant no touch-and-goes, which wasn't really in our plans anyway. Second, we had to de-ice the plane, which is somewhat a pain. Plastic bags of warm water to melt and loosen the ice, then wipe it off with a towel. Fortunately being in Colorado, the sun does a pretty good job of melting frost and ice by mid-morning, but that only works where the sun hits. I pulled the plane out and turned it around so the sun could shine on the shady side of things, but it still took a bit to get things clean. And for whatever reason, I simply wasn't clicking on all cylinders today. Nothing major, just forgetting stupid things like my run-up checklist and just being a bit behind in thought.

We took off and headed east. When you're climbing in a small plane like a Grumman, you have the throttle full as you need all the power you can get. Once you're at altitude, you back the throttle off a bit, set your pitch and fly straight and level. This plane today did not want to fly level for love or money. It just wanted to climb. Maybe the cold air had something to do with it, but it seemed every time I looked at the altimeter, I had climbed 100'. Trim? Didn't matter. No amount of nose-down trim kept this bird from climbing.

Once en route, the plan was to pick up flight following from Denver control on our way out to Limon. Flight following is just an extra set of eyes on you as you fly to your destination. They'll alert you to traffic nearby and things like that. They don't necessarily tell you where to fly, though they will if you're in a congested area to keep you out of the way of other traffic. You call them up on the radio, they give you a unique code to punch into your transponder so they can identify you specifically on their screens, and you go about your flight. They were rather busy today, so they first took forever to get back to us when we called them. When they did, they gave us a code to enter. Simple. Nope. The transponder in the Grumman is a touch screen. I don't know whose brilliant idea it was that touch screens in a bumpy airplane cockpit were a good idea, but I'm pretty sure they were also responsible for screen doors on submarines. But, noooo.... that wasn't enough. In addition to having trouble hitting the right buttons on the touch screen, said touch screen decided it was going to malfunction. When you did finally land your finger on the "5" button, "3" showed up on the screen. It was a mess. All the while ATC is getting increasingly frustrated with us because we're not yet showing the requested code. After about two minutes of trying, we gave up and cancelled our request for flight following. So much for that.

Back to the task at hand, flying to Limon via GPS. It's simple, right? You have GPS. You enter your destination. You press "go to." A magenta line shows up on the screen. You follow the magenta line. Apparently not. You follow the magenta needle that shows up on your heading indicator. I did not know that, and my instructor was a bit annoyed at that. "What has your other instructor been teaching you?" he asked rather incredulously. Apparently it's not enough to fly the same heading as the magenta line though you're maybe a mile or two one side or the other of it. "Fly the needle" means you keep the plane directly on that magenta line. Yes, that's definitely how you want to do things when flying on instruments, and maybe this was a difference in expectations where my CFI was looking for instrument precision on this flight and I was using them as general references in conjunction with VFR rules.

Be that as it may, we made it out to Limon. This was my first time flying to an un-towered airport. That means there's no air traffic controller telling you where to go. You have to make your own decisions on which runway to use, identify other traffic that's also flying around the airport, and most importantly, don't hit anyone in the process. I have the opposite problem from a lot of students. Many who fly out of un-towered airports cannot grasp radio calls to air traffic control. I'm the opposite. Communications at un-towered airports to me seem a bit wild west. There's structure, but there's no readback. It's all on you. And while it's not quite a foreign language, it's certainly a very distinct dialect. There were a few planes in the pattern at Limon today, so it was definitely an experience.

Landing at Limon was okay. We opted for a full stop/taxi back landing due to the wet runway conditions thanks to melting snow. No big deal. The runway was plowed. The taxiway, on the other hand. I got the nosewheel stuck in a pile of slushy snow that took some doing to get out of. Just one more thing to knock me off my game.

We decided we were both frustrated enough for one day, pointed the nose west, and headed home. Not my best outing. Lots of little things. Some out of my control, some that I simply didn't execute. But in the list of unproductive lessons I've had, this one sits high on the list.

Lesson 72 - Short Cross Country (redux)

Today was a repeat, a cross country flight out to Limon, CO. I flew this flight earlier this year with my old CFI before he left for the airlines. However, school policy says I must have flown any potential solo cross country route with my current CFI, so here we were planning another short hop out to Limon. I "just" need my solo cross country to wrap this process up, so whatever I can do to make that happen, I'm going to do it.

On one hand, having to re-do this flight is bit of a bummer because in some ways it was just burning money to satisfy the legal or other policy requirements of the powers that be. No one likes wasting money, even if the views are great! On the other hand, my this was only my fourth flight with my new CFI, and he hadn't had a chance to fly with me long distances yet. He's still getting used to me, getting a feel for my strengths and weaknesses. Its his name on the endorsement, and I'd want the same of any student if I were teaching. Besides, my last flight to Limon was, well, let's just forget that one, shall we?

I was a bit unsure of the winds forecast for the day, so I planned a flight to Limon and also to Fort Morgan, where earlier in the week the winds looked a bit more favorable. I figured we'd see what the winds were doing when we took off and fly to one or the other. The winds today favored Limon, so that's where we went. Today's flight was VFR (visual flight rules) which means you're navigating by what you can see out of the window. Yes, I have GPS in the plane, and I had the flight pulled up on my iPad to keep track of where I was, but I was not flying it by "magenta line." My job was to pick easily-identifiable landmarks along the route to get me to where I am supposed to be going. Old-school pilotage. Early on in my training, my original CFI had me draw up a flight plan to Limon using landmarks on the ground. When I looked at the map for identifiable landmarks between here and there, I got the joke. It's all farmland, and from 3,000' above the ground, all the farms look alike. I drew up a plan that followed the roads, since they were easily seen, if not necessarily the most direct route. My old CFI and I never got around to putting that plan into action, so I revived it for this trip. (My previous flight to Limon relied more on electronic navigation to get me out and back.)

With the flight plan loaded into the tablet and sun shining, we set off. My soft-field take-off technique still needs work. I need to get better at staying in ground effect to build up speed before climbing out. (Part of that is that I also still need to get used to climbing with 25 degrees of flaps. All of my climb-outs today were slower than I'd like them to be.) Once airborne, I flew to Parker, then down to Franktown where I picked up highway 86 which runs out to Limon, and followed that all the way out.

Approaching Limon, my instructor dialed in Limon's airport on one of our GPS units to figure out what our descent rate should be. I haven't had the chance to play much with this aspect of the technology in the cockpit yet, so this was a bit of an electronics education for me. From where we were, it told us we needed a 500 foot-per-minute descent rate to get to pattern altitude over the airfield. I pulled out just a bit of power, set trim, and enjoyed probably one of the smoothest descents from altitude I've flown. (I'm really liking the Archers.) It was almost like having autopilot, which I'll get to momentarily. In any respect, it was almost like I knew where I was going and what I was doing!

I did mess one thing up. I descended to 6,400' to overfly the airport, since that's the elevation my instructor dialed into the GPS. Normal procedure when overflying an airport is to do so 500' above pattern altitude, which is 1,000' above the field elevation. My brain, then, decided that 6,400' was 500' above traffic pattern altitude, so once over the field, I started descending an additional 500'. Alas, my brain was wrong. Field elevation at Limon is 5,400. Traffic pattern altitude is 6,400'. I'm pretty sure my instructor said that, and I'm pretty sure when I looked up the airport I saw the field elevation, but at that point in time, my brain was having none of it. It made up its mind, and it was wrong. Fortunately, it just meant that as I started descending down to around 6,100', my CFI reminded me that I was quite low enough for what we were doing, and perhaps I should level off a bit.

The landings were pretty good. I was working on my short-field technique without necessarily making a point to do it, just that we only had 4,600' of runway and we were doing touch-and-goes, so I needed to land as short as possible so to have enough runway to get back up again. There aren't thousand-foot markers on this runway, so I really didn't have a specific aiming point. Having said that, I didn't really think I floated unnecessarily far down the runway, and had I been concentrating on making a specific point, probably would have made it easily enough.

My climb-out performance still wasn't what I was hoping it would be. It was warm, but not hot, but I seem to have been given a choice--speed or rate-of-climb. If I wanted to climb at 300' per minute or more, my speed was 60 - 70 knots at the most, which is just too close to stall speed for comfort. I'm still not sure where that's stemming from besides me not being used to flying with 25 degrees of flaps. That's something I'm going to work on next time. It's probably just one little thing, but I need to figure out what it is. Outside of that, I only had one approach that got too low and slow for my tastes (and my instructors). I was getting ready to go around right when he said "go around." He said he wanted to give me a go-around anyway to see how I handled it, so there's that. I think on that landing, I put in full flaps just a touch too early, and did not put in enough power in return.

We left Limon to head back to Centennial. I didn't have a specific flight plan for that beyond "go back the way I came." Nothing was in the iPad, so I just followed the road. I had thought earlier in the week that I could do some instrument flying and foggle work this trip, and was contemplating pulling my foggles out of my bag when my instructor asked if I had ever flown with autopilot. I hadn't, since neither the Grummans nor Cessnas that I had flown actually had working autopilots. He suggested I dial it up to see how it works. That sounded just as reasonable to me because my check ride examiner is going to expect me to know how to use the autopilot if it's in the plane I do my check ride in.

It's actually pretty simple. You dial in the heading you want to fly and hit the "heading" button. Then you get to the altitude you want to maintain and hit the "altitude" button. The computer takes it from there. Need to change course? Just enter your new heading. Need to climb? You can turn a knob to increase your rate of climb to get you to a new elevation. Easy. "Sit back, relax, and enjoy the flight." Well, not quite. This flavor of autopilot will maintain your heading and altitude. It does not control your power or speed. If you reduce power, which tends to reduce altitude, it compensates by adjusting the pitch, which impacts speed. If you it a downdraft and lose altitude quickly, it doesn't see that as turbulence, but just a need to get you back up to the requested altitude, which it does by increasing pitch which reduces speed. While flying with the autopilot engaged and talking with my instructor about other things, my airspeed was quietly creeping down--almost to stall speed. Fortunately, the pilot can (a) overpower the autopilot, and (b) disengage it entirely in those situations. My instructor showed me where the "disengage" button was, and I flew manually the rest of the flight. Lesson: Autopilot allows you to take your hands off the controls. It does not mean you take your eyes off your instruments.

With that lesson learned, we called Centennial, got clearance to land and returned home. I was a bit lower than I should have been on my approach, which kinda bugged me that I let that happen, but I'm not going to beat myself up over it. On my landing at Centennial, I flared too high because I was used to the narrower 60' runway at Limon and thought I was lower than I was. As a result, I floated further down the runway than I wanted to. (Definitely not a short field landing this time.) It wasn't a bad landing, but I wasn't as in control of it as I would like. But if that's the worst that happened, it's a good day in the air.

Wednesday, August 9, 2023

Lesson 60 - The Long Cross Country

With the initial solo stage now behind me, it is now time to focus on the last significant part of this journey, the long cross country flight. I've written before that "cross country" is kind of a misnomer. For training purposes, a "cross country" flight is a flight to any airport more than 50 nautical miles away. The "long" cross country is a flight of longer than 150 nautical miles, with at least three airports, and a distance of at least 50 nautical miles between two of those stops.

My instructor and I planned on flying east to Fort Morgan, then continuing to Akron, then return to Centennial. Flying the plane is only part of the process, arguably the smallest part of the process. The long cross country is all about planning. Weight, waypoints, navigation, fuel, plane performance, etc. It's the "make sure you can make it safely" part of flying that we don't often think about as passengers. In the digital age, this kind of planning is easily done using software like ForeFlight, but--naturally--instructors have a mean streak and want you to learn the old fashioned way with charts, plotters, and paper. (Okay, it's old school, but you really do need to understand how to do that so you understand why ForeFlight gives you the numbers it gives you. That, and there's a geeky quality to showing up with a bunch of paper for each leg with all the info written out for you.)

I arrived at the airport plan in hand. Well, you know what happens with plans. The first thing my instructor and I do is look at the weather. Fort Morgan is fogged in. "Primary target covered by fog. The decision to proceed is yours." (I told you there would be frequent "Airplane!" references throughout this blog.) After a bit of deliberation, we figured the fog would burn off in an hour or so. Let's just fly to Akron first, that way when we leave for Fort Morgan, the fog will likely have lifted. It made sense, so we rolled with it.

Only one minor little hitch. In the digital world, to reverse the direction of my flight, all I have to do is hit the "reverse direction of flight" button. Presto, change-o, I have all new numbers for headings, times, etc. I didn't do this plan digitally. It's all on paper. As a result, I spent the time waiting for the fuel truck to arrive frantically re-calculating my route. Because of wind speed and direction, it's not just a matter of turning your heading 180 degrees.

We took off, and navigation by the waypoints I had chosen went fairly easily. I was worried the large radio tower I picked would be difficult to find, but the fresh snowfall allowed me to easily see the antenna against the snowy ground. I'm not sure it would be quite as easy in the summer, but it worked today and that's all it needed to do.

Arriving at Akron, we discovered that the runway had not yet been plowed. Planes had been taking off and landing, but it was packed snow on the surface. My instructor and I decided that a "full stop and taxi back" landing was off the table. We weren't gonna stop. We weren't even gonna slow down. Touch (very lightly) and go. Neither of us had any desire to slide off the side of the runway today.

Leaving Akron, I turned towards Fort Morgan, which isn't really all that far away. Fort Morgan sits beside the South Platte River, which was what was causing the fog. There was still a healthy amount of fog right in the river valley, but--as my instructor predicted--the fog had lifted from the airport. What's more the runway had been plowed. We did a stop-and-go so we could say we actually stopped, then raised flaps, applied power, and off again for home.

The flight back home was routine. I again used that same tall radio antenna as a landmark to get me back and found it without issue. With this flight, I was able to knock out the required long cross country requirement with an instructor. There would still be 5 hours solo cross country, but that will come later.

Lesson 59 - Zen Interrupted

I don't know that I really intended to have back-to-back solo flights, but--hey--I have the endorsement, I may as well enjoy it, right? My previous solo flight was more of a "you're finally up here by yourself" flight, so this time it was time to get to work. Today was "brush up your landings" day.

The pattern at Centennial was full, so I flew out to Spaceport. The winds were out of the south, so I thought that would be perfect. Straight down the runway. I get out to Spaceport, call the tower, and ask for touch-and-goes. They say sure. Fly to Bennet and straight in on runway 26. Um, the winds are straight out of the south. Why not 17? No. That would make too much sense. Sorry, they're using 17 only for departing traffic. Anyone wanting to do pattern work will be using 26. Landing on 26 with winds out of the south means a crosswind, and a direct one at that. I ask for an update on the winds. 170 degrees at 8 knots. With my solo endorsement, 8 knots is the maximum crosswind I'm allowed to land in if I'm by myself. I was "legal." Unsure, untested, but legal. I figured I'd have a go at one, and if I didn't like it, I'd go around and just depart to the south.

I have actually flown crosswind landings many times on my simulator at home. I've got different scenarios set up with varying degrees of crosswinds. I'll scroll through them as I practice so to mix things up a bit. It's good practice to build muscle memory, but the sim is never "quite" like the real thing. Fortunately like the sim, today's wind was a steady 8 knots, so there wasn't a whole lot of adjustment I needed to do to stay on centerline. The key is to crab the nose into the wind just a bit so you keep your course over the ground in line with the centerline of the runway on your approach. Once you're on short final or crossing the threshold of the runway (wherever you feel comfortable), dip your wing into the wind and apply opposite rudder. Dipping your wing into the wind creates a turning force to combat the wind, and opposite rudder points the nose of plane straight down the runway so when you touch down, you're rolling in the right direction, not headed off to the side. It's a bit of a dance and one that definitely takes practice to get right.

I'll be perfectly honest and say I surprised myself on my first landing. It was rather smooth and (mostly) on center. I figured that was good enough to build upon, so I stayed in the pattern and flew a half dozen or so more landings. None were "perfect," but all were pretty decent and I felt in control of the process the entire time. Today was definitely a confidence builder. Good solo flight getting out to Spaceport, good crosswind control on landings, I was actually reveling in the moment.

Feeling good about things thus far, I figured I'd cap the day off by flying solo over my house. It's on the way back, so I wasn't going to be going out of my way or anything. I found the major cross street near my neighborhood and lined up to fly over it. I was thinking about quickly texting my wife to have her look out the window (voice to text in a loud cockpit would be interesting, but no worse than it butchers my usual messages). It was just me, my thoughts, and the cool notion of waving to my family as I flew over the house.

"Three Eight Eight Charlie, are you on frequency?"

Oh, crap! There's that little thing you have to do called "talking to the airport you want to land at." I was so caught up in the zen of the moment I forgot I still had real work to do. Fortunately I had not yet entered their air space; I was still a few miles out and flying a course which would have me skirt the outside of it. However, I'm in a trainer whose call numbers ATC sees multiple times per day as student after student flies the plane out and returns to the airport. They had every expectation that I was going to turn inward at any moment.

The thoughts in the previous paragraph raced through my mind in about half a second as I was snapped out of my state of zen, and I told ATC that I was indeed listening to them. They instructed me to continue to runway 17-left to land. By this time I was nearly over my house, so I just waved quietly as I flew overhead.

The takeaway? Never get so caught up in the fun that you forget you still have a job to do. I didn't bust any airspaces or break any rules, but I was not giving the primary task at hand the attention it needed. I'm not naive enough to say it will never happen again, but it was a glimpse into how easily it is to get into that mind space.

Tuesday, February 21, 2023

Lesson 58 - All By Myself

A student pilot's first solo is a momentous occasion. It's the first time you're at the controls without a safety net. For most students--me included--that first solo is "just" take-offs and landings in the traffic pattern at the airport. It's also dome with the instructor flying with you for part of the lesson then hopping out of the plane. That's not to take away from the achievement of the first solo, but it is also a very safe "close to home" flight and your instructor is still there in the plane with you at first with the preflight and doing some take-offs and landings to get you warmed up.

Today's solo flight was all me from the start. I had to check in with my instructor briefly (school policy), but that's just to confirm weather and make sure I've got all the stuff I need to solo (medial certificate, logbook with solo endorsement, student pilot license, photo ID). He also asked what I was thinking of doing. I told him I wanted to fly out to the practice area and just get a feel for how the plane responds with just one person in it. I also wanted to just try some turns and climbs by myself just to get a better feel for how they "feel" without my instructor in the seat next to me wondering what I'm doing. Some things are just easier to try on your own. He said "have fun" and I headed out to the ramp.

One of the first things on my preflight inspection is to check the fuel. This way if I need to add, I can do the rest of the preflight while waiting for the truck to pull up. I was less than half in each tank, so I called and proceeded with my preflight. Thirty minutes later, the truck pulls up. This gave me time to get things situated in the plane, including a picture of the plane which my daughter had painted in celebration of my first solo flight.

In many ways, today's flight was very similar to the first time I flew the Grumman earlier this Spring. That flight was "back to basics," so I could get the feel of the new plane compared to the Cessna I had been training in to that point. Climbs, descents, turns, stalls, etc. That's pretty much exactly what I did this time, except I was all alone in the plane. I didn't do anything crazy. I didn't want to. Today's flight was me--for the first time in my life--in the left seat of an airplane doing what I wanted to do, when I wanted to do it. I was flying for the sheer joy of flying. It was what I've dreamed of doing since I was a kid. I flew, took some pictures and some video, and just reveled in the moment, soaking it all in. It was wonderful!

After flying around for a bit, I decided it was time to head back to the airport. Obviously I'd have liked to stay out longer, but time is money and there was nothing to be gained today by more time. This was a taste, a tease, incentive to keep seeing this process through. I flew west to I-25 at Castle Rock and turned north. The winds favored landing on runway 35, and I knew if I came up Parker Road as I normally do when coming back from the southeast practice area, they'd route me to runway 28, and I wasn't in the mood to deal with crosswinds. And besides, 35 right is 10,000' long and 150' wide. For a student solo, that's a pretty big target to hit. I contacted the tower, turned north, landed without incident, and my first full solo flight was over.

I have to admit, it was a little weird walking back into the pilot's lounge, placing the notebook and keys for the plane back on the shelf and just leaving. No debrief, no nothing. Flight's over, go home. The flight was over, yeah, but I was still flying pretty high the rest of the day.

Tuesday, December 27, 2022

Lesson 57 - A Little Night Flying

After my previous lesson, my instructor texted me, "hey, how 'bout a night flight next? It's supposed to be warm." I looked at the long range forecast, and while Monday was indeed going to be warm, it was also going to be windy due to a system moving through. I suggested moving our Thursday lesson to the evening since I happened to have the day off from work that day. It wasn't going to be warm, but the winds looked reasonable. We scheduled for 5pm, with being the middle of December was well after sunset.

It was a bit chilly, so my instructor and I tag-teamed the preflight inspection in order to get through things just a bit faster. Fortunately, the plane was parked right under the only light pole on this end of the field, so we could see what we were doing. We were quick, but thorough. I often read stories of folks rushing through their preflight inspections in the cold and at night, but we still made sure we didn't forget anything, except remembering that I had gloves in my pocket.

We took off and headed south because I wanted to get away from the city lights for a bit. Flying at night is "easy" when flying over the city because the lights give you a good sense of a horizon. Flying in the middle of nowhere takes that visual cue away and I wanted to experience that. I got more than I bargained for. We picked up Parker Road, which is our typical route south to the practice areas. Not that we were going to be doing and ground reference stuff at night, but it was an easy landmark to follow into the darkness. Before too long, I noticed that my view forward had gotten very dark, indeed. That's to be expected, as there's not a whole lot out there. Still, I should have been able to see some lights somewhere. I glanced down at the ground beneath us. Recent snows still laid on the ground so I had a bit more definition on the ground than I may have had without it, but something still seemed a bit off. I glanced at my wingtips. The strobes were picking up moderate snow. Apparently there was a line of snow showers to the south of town, and I had just flown into them. We weren't in the clouds because I could still see below me, but we were enough into the thick of the snow where visibility was quite compromised.

My first thought was to do a coordinated "standard rate" 180 turn and head north. We were flying into IMC (instrument meteorological conditions), and that's what you're supposed to do in that situation if you're not IFR rated. I'm not. My instructor is, however, and he seized upon the opportunity. "Give me a steep 360 to the right." A what??? We're flying in IMC and you want me to do a steep turn? But--hey--he wants to walk away from this flight as much as I do, so he wouldn't have me do anything to put us at risk. Okay, I don't have reference outside the window, so look at the heading indicator, not which way I'm flying, rock the wings to 45 degrees, hold altitude, watch the heading indicator and attitude indicator, and make a 360. About halfway through the turn, I see hints of lights sweeping by out of the window, though not necessarily in the direction I thought they should be. I checked my instruments and I was where I should be. No sooner had I finished that turn, my instructor had me do another steep turn to the left. Same thing. Watch my heading and attitude indicators, don't lose altitude, and--again--about halfway through, I caught hints of city lights sweeping through the window. And--again--not in the direction I thought they should be. But my instruments were exactly where they needed to be for the maneuver.

"So, what'd you think?" he asked me. It wasn't scary or unnerving. I've flown steep turns and I've flown without being able to see out the window, so it wasn't anything particularly unusual. However, the disconnect between what my instruments were showing and what I thought I saw out the window was quite sobering. It was a quick (and powerful) introduction to spatial disorientation at night. The lights play tricks on you. Trust your instruments. We flew around a bit more in the almost complete darkness looking down for hints of roads or cars on them, and then by GPS to get us headed back to the airport to do some landings.

You would think an airport beacon would be easy to spot. After all, that's why airports have beacons--so planes can easily spot the airfield. By now we had flown far enough north to where we were out of the weather, so we had a good view of the city lights underneath and ahead of us. Could either of us find that stinking beacon? Nope. I found a dark area which I presumed to be Hess reservoir, then found the power lines that cross south of the field and then flew that direction because I knew I could find the runway from there, even without seeing the airport beacon. I called the tower, they cleared us to land.

Prior to flying this flight, I had spent some time on my simulator doing night landings. I wanted to give myself a sense of what to expect. No, the sim isn't exactly like the real thing, but I figured it would point out things I'd want to pay attention to. The biggest issue I had on the simulator was keeping the centerline lined up. Also, a lack of peripheral vision as a reference for when to time my round-out and flare. I found in the real world, with depth perception to help out, keeping things lined up on centerline was easier than on the sim. Still not easy, because you only have lights on the edge of the runway to help, but easier than on the sim. Not having that peripheral vision to the side to time your round-out and flare, though, that got me every time. We did four landings at this point, and I flared too high on each and every one, causing me to lose airspeed and stall just a bit higher than I wanted to over the runway. "Smooth" was not part of the equation. After our forth landing, I decided I just wanted to fly and enjoy the lights of the city, so I asked the tower for a departure to the west, which they gave me. Once headed west, I handed the controls over to my instructor, pulled out my camera, and started taking pictures. It was a few days before Christmas, and all the neighborhoods were lit up. It was pretty cool.

Completely unrelated to flying, it took me a bit to get the settings on my camera set to where I could get clean, well-exposed photos. I found that even with a good zoom lens, we were simply too high to get the neighborhood lights in any detail, so I just stuck to wide city shots. I also learned my iPhone takes much better night pictures than my old Canon DSLR. Go figure.

After I took a handful of pictures, I took the controls and brought us back to the airport for one last landing. This time, I was going to hold just a little bit longer to try to time my round-out and flare just a bit better. I lined up, held things off until the last moment, rounded out, and THUD! I landed flat on all three wheels. Better than landing on the nose wheel first, but maybe I over-compensated just a bit.

I've got one more required night flight, and it has to be 100 miles minimum. I also need 5 more night landings, so my instructor suggested an idea for our next night flight, a tour of a lot of local airports. I'm not sure when we'll get that scheduled, but I'm looking forward to it.

Sunday, December 11, 2022

Lesson 56 - Brush Up your Crosswind

After my previous lesson, I wanted to continue to work on my instrument flying, and also if practical, work on my crosswind landings. At this point, every lesson should check off more and more of the requirements for my final check ride. Get those out of the way, then just polish the skills that need polishing (like landings). Then I'll be ready for my final exam, so to speak. I checked the weather when I woke up, which had the winds at 7 knots out of the west. That was perfect for working on crosswind landings. By the time left for the airport, the winds had picked up a bit. By "a bit," I mean 14 gusting to 20, and still out of the west. If I were flying solo, that would be a hard "no go" at that point. The club rules dictate a maximum crosswind of 8 knots, and I'm more than fine with that.

I sat down with my instructor, half expecting to come to the conclusion that the winds were crap and we wouldn't fly today. Nope. Today I was flying with my secondary instructor who likes his students to really know how to handle crosswinds. The 8-knot rule is for student solo, not for students flying with instructors, and he saw this as a perfect opportunity. Gusty crosswinds, but still within the minimums for the plane itself. I couldn't come up with a reason not to have a go, because it's definitely something that makes sense to learn with an instructor sitting next to you. We figured we'd do a little navigation work under the hood and then see if ATC would let us do some touch-and-goes before calling it a day.

We got in the plane and got the latest weather, which indicated the winds had calmed down just a bit, now down to 10 knots gusting to around 17. We decided to switch things around and see if we could do touch-and-goes first since 10 gusting to 17 was preferable to 14 gusting to 20. ATC obliged, and we were soon up in the pattern setting up for crosswind landings.

I've written about this in the past. I've drilled crosswind landings in the past. Today, they kicked my butt. I was fighting the wind today. Part of it stemmed from my instructor having me fly these without setting any flaps, so my approach speeds were faster than I had done in the past. The challenge there is that instead of using the flaps to create drag to slow down, you pitch the nose of the plane up a bit higher to slow down. When you do that, you become a bigger target for the wind. The gusts were also more unpredictable than just a stable crosswind, so my adjustments were not as good as I wanted. Add to that I had a tendency on round-out to want to level the wings, which is not what you want to do in a crosswind situation. Still, I pushed through four crosswind landings, in which I did manage to set the plane down on the runway more-or-less in line with it, but definitely not on center. It was, however, a significant crosswind, so while I won't say I did good, I won't say I did horrible, either. Definitely something I will work on again (and again) as conditions allow. My fifth attempt at landing resulted in a go-around because ATC had me do a short approach which left me too high. I slipped down to the proper altitude, but I was too fast and unstable for comfort so I waved off. We then departed to the east for some instrument work.

Today, I wanted to work on dialing in and tracking VOR navigation signals. I knew I could do better than my last time up, and wanted to prove to myself that I actually did know how to do it. I was back under the hood instead of using foggles because that's what the desk had available. I much prefer foggles. The hood kept sliding down, causing me to have to crane my neck up a bit to see the instruments. But that's neither here nor there. I felt I did better today with things, but I don't think I was quite as task-saturated, either. I still need to get better at dialing in VOR and GPS information in small spurts so not to take my attention away from keeping the plane on course. That comes with familiarization with the navigation electronics on the plane, which I'm just now starting to play with.

I tracked the VOR signal out to a small private airfield, arriving about a mile south of it, which in the grand scheme of things is pretty good. I switched to GPS navigation and followed that back to the airport. Along the way, my instructor told me to close my eyes while he put the plane in what pilots call an "unusual attitude." This is where the instructor (or examiner) takes the controls, puts the plane in a steep climb, bank, dive, or otherwise not ideal situation and says "fix it." You've got to quickly assess the attitude of your plane and the steps needed to correct it. Nose down too much, you've got to raise it. Nose up to high, you've got to lower it. Watch your airspeed. Level the wings. Work your way back to your course and altitude. I will admit this was fun, and I corrected us with relative ease.

When the GPS showed me about 10 miles out from the airport, I called the tower, took off the hood, and flew the approach visually. By now the winds had shifted direction so they were coming more or less out of the north. Yay! No more crosswind!!! I set us down on the runway with comparative ease to my earlier crosswind endeavors, to the point where my instructor later called that landing "pretty much perfect." Coming from him, that's high praise indeed. When he says that about my crosswind landings, I know I'll be ready for my check ride.

Thursday, December 8, 2022

Lesson 55 - Where Am I???

With the first solo out of the way, I'm actually coming down the home stretch. That's not to say I'm going to be finished tomorrow by any means, but now it's just a matter of planning the lessons so they start checking off the required components needed for my final check ride. Those include night flights, 10 hours of solo time, and "cross country" flights, both with an instructor and by myself. Also included in that requirement is that I fly at least 3 hours in simulated (or actual) instrument flying conditions. We decided today would be a good day to work on that.

I prepped the plane, we took off, and once I reached cruising altitude, my instructor pulled out the "foggles," and had me put them on. Foggles are essentially clear glasses with the top half of the lenses fogged over so you can't see anything but a blur of light through them. The bottom is clear so you can see your instruments. These are different from the hood I wore my first time, which is essentially an oversized golf visor. The foggles have the advantage of letting light through, which does a better job of simulating flying in the clouds where you're still surrounded by light, but you just can't see anything through it.

I remembered from my first time flying by instruments that I was over-controlling the plane. I was turning too steep and climbing too fast, so I overshot everything. I worked the simulator a bit between then and now, and trained myself to make smaller adjustments. This paid off. My instructor had me climbing and descending, and also turning left and right. These I did with relative ease this time. Smaller control movements meant I didn't overshoot.

Next, my instructor had me climb and turn at the same time. This is not quite "rub your belly and pat your head," but it still required a fair amount of concentration. I did okay with this early on in the process, but when my instructor had me making a series of turns and climbs in succession, I started to lose my bearings and began missing my targets. Now, some instructors would see this and maybe dial it back a bit to get me back in my comfort zone. Nope. Instead, he decided to layer VOR navigation into the mix, since when flying by instruments, this is one of the tools a pilot would be using to navigate.

I have practiced VOR navigation on my simulator, and I tracked a VOR radial my last time under the hood, so this wasn't necessarily new to me. What was new was having it layered in with not being able to see anything but my instruments, and having to tune in the frequencies and radials while maintaining flight based solely on the instruments. This meant for a student pilot who is relatively inexperienced with this workflow, spending an inordinate amount of time looking at the radios and VOR gauge, drawing one's attention away from the other gauges, particularly the attitude indicator which is really the best visual reference you have to what the plane is doing. You can't see outside, so there's no horizon in your periphery that can guide you. Combine that with having to track this radial, then that radial, then turn and fly towards the VOR station and a whole lot of other more-or-less unfamiliar (and certainly unpracticed) maneuvers, and things went sideways fast.

"You don't know where you are or what you're doing, do you?"

Yeah, that's a pretty fair assessment at this point. I had no concept of which way the plane was pointed. Yes, the heading indicator showed 90 degrees (east) but my mind simply couldn't picture which way that was. I was utterly confused. My altitude control was suffering mightily as well. At least I knew which way was up, but I was just having a hard time keeping level flight.

You often hear about "spatial disorientation" when pilots fly in the clouds. Pilots get into those circumstances and simply don't believe their instruments. I experienced that today. It's not pleasant. It's easy to see how so many pilots crash their planes in cloudy/foggy conditions. I'm not gonna lie, it rattled me. Not to the point of being afraid or incapable of continuing, but because of how quickly task saturation set in and got me to that point.

This was drinking from the firehose again. I've had a small handful of lessons like this; lessons where I'm pushed well past my comfort zone. We then dissect things and work on the various skills that come into play in that scenario. After I got thoroughly disoriented, my instructor had me take the foggles off. Since it was the addition of VOR navigation and me trying to wrap my head around that which seemed to be the tipping point, we worked on VOR navigation where I could see out the window. I'm not confused by it, but it's not yet second nature. That will come with time and practice, and when it becomes more second nature, it will be easier to incorporate it into the workflow when I can't see out the window.

We returned back to the airport, where I flew a pretty decent approach, but we had a fairly significant crosswind which I struggled to keep up with. Not sure why, because I knew it was there. I just didn't do a good job at all of dealing with it. Something else to work on.

The race is on...

Teaching students to fly is the most common way for pilots working their way to the airlines to build the requisite time required, which is 1,500 total hours. Well, my instructor hit that magic number and is headed to the airlines on March 10th. So, the race is on. Can I get through all my requirements and be ready for my check ride before he leaves? Time will tell.

Thursday, November 17, 2022

Lesson 54 - First Solo

A student pilot's first solo is arguably the most significant milestone in one's journey to becoming a pilot, or at least one that does not involve passing the FAA's check ride. It is the first time you're truly on your own. There's no safety net of an instructor sitting next to you. Either you know it, or you figure it out really quickly. The student's first solo is in most cases the student flying a few circles in the patten with the instructor who then hops out and sending the student back into the pattern for a few more landings on his/her own. While it's usually a big deal on the emotional front, from a practical standpoint, it's a very simple outing. You basically never leave the airport. With my stage check out of the way two weeks previous, I just needed a day with sunny skies and calm winds to do my first solo. Last week was too windy. I checked the airport forecast for Wednesday. It looked good. Alright, I'm going to knock this one out.

Except, they closed the parallel runway at Centennial. Don't know why, but that means no pattern work, so no solo at Centennial. I arrived at the airport not knowing if there was a plan B, or if we were just going to have to do something else. My instructor said we'd instead head out to Spaceport instead, because the winds, while higher than at Centennial, were still within minimums. I prepped the plane and we took off to the east. Once in the air, I contacted Spaceport. Their pattern was full. What's more, the winds had kicked up beyond the club limits for student solos, so that wasn't an option. My instructor checked his phone and says the winds are calm down in Colorado Springs. We turned south. At this point, I still don't know if I'm actually going to solo, but I figured we's see where this went. We call Denver Departure for flight following down to the Springs, and set the VOR to navigate to the airport.

We arrive in Colorado Springs and land on the east runway (17 left). The approach to this runway took me directly over my in-laws' houses, which was cool. This runway is 150' wide and 13,000 long, so it would have been next to impossible to miss it. Still, my instructor was (rightly so) being a stickler for hitting the centerline. Between the glare from the noontime sun and the skid marks from landing jets, the centerline was difficult to make out, but that's a poor excuse. Centerline tracking is important. At this point, I wasn't sure if I was blowing my chance at soloing or not. On my forth touch-and-go, my instructor called the tower to inquire about landing to let him off. They had us fly and land on the west runway (17 right) so I could drop him off. After the gratuitous "first solo" photo of the empty seat next to me and my instructor on the tarmac taking my picture, I throttled up and headed back out to the taxiway. This was it.

The plan was to do three or four landings, then pick up my instructor and head back north. Colorado Springs' traffic control is a bit different than Centennial in that the ground controller does not hand you off to the tower. You follow the ground controller's instructions up to the hold-short line on the runway, then you switch over to tower frequency and let them know you're ready. Nothing I couldn't handle, but a reminder that I didn't have the "home field advantage." I took off, having to confirm with the tower that they wanted me in a right pattern because I knew I asked, but I wasn't sure I remembered the answer. Nerves. I told them I was a student solo, and they said no worries.

My first landing was pretty smooth. Not perfect, but on center and on speed. I lifted off again. On my next approach, I was following another student pilot from one of the bigger schools. They were doing a full stop landing, and decided to take their own sweet time getting off the runway. They were still on the runway when I was approaching the threshold, so ATC told me to sidestep to the right and go around. Kinda figured that was going to happen. Had I realized they were full stop when I was on my downwind, I would have extended to give them a bit more time, but oh well. Go-arounds happen, and that's why we practice them. My third landing was my worst of the day. For some reason, I floated down the runway in ground effect for what seemed like forever. I was at 65 knots and not slowing down or going down. I jiggled the throttle thinking maybe it wasn't at full idle. Maybe that was it, but whatever it was, I lost that last bit of airspeed and bounced on the runway before I was ready. On the second bounce, I decided that was enough of that nonsense, stuffed the throttle back to full and started climbing back out. My fourth landing, butter. Absolute butter. I was almost bummed that I was solo on that one because it was definitely worthy of sharing with someone.

We flew back to Centennial, where ironically my instructor handled the landing because there was a corporate jet landing right behind us so we needed to do a high-speed approach. I know the theory, and goodness knows I've accidentally arrived at the runway threshold at 95 knots at more than a few points in my training, but the resulting landings were abysmal. I was happy to be along for the ride on this one, studying the steps so I can practice them later without a jet riding my rear end. Once on the ground and back in the terminal, I had a very brief moment for the ceremonial shirt tail cutting and photo with my instructor, but we were at this point already an hour late for his next student, who--thankfully--was in the same plane, and very patient.

Take-aways of the day. First, I did it. Not that I was worried, but I did it. That by itself is an achievement. Second, things went wrong (as they will) and I handled them well. ATC said "go around," and I was able to calmly do that. I bounced a landing, recognized the danger, and recovered for the go-around. And I re-grouped after that and absolutely nailed my last landing. Lastly, though completely unplanned and rather impromptu, I think flying down to Colorado Springs added something to the day. It made it a bigger event than just flying three loops in the pattern at the home field. I soloed at an airport I had never been to before. I don't know how big a deal that really is, but to me, it showed that I can enter an unfamiliar airspace and handle it quite well even under a bit of pressure.

There seems to be two schools of thought on when student pilots solo. Some believe a student should learn how to land right out of the gate, thus get to solo stage between 10 and 20 hours, under the theory that soloing will sharpen those skills as the student pilot sorts things out for themselves. The other (the one embraced by my school) is that students should have a fairly firm grasp of many aspects of flying, including unusual circumstances prior to being given the keys to the sky. I think the former style puts the student in a "sink or swim" environment. Certainly the instructor has faith the student will do well enough or they wouldn't have signed off on it. But does the student? Yet, perhaps a student who completes his or her solo facing a lot of personal apprehension finds an amplified sense of accomplishment having completed the solo despite that apprehension, an "I didn't think I could, but I did!" mindset. There is something particularly rewarding there.

When looking at my experience through that lens, my solo may be seen as somewhat anticlimactic. There was no "I didn't think I could" aspect of things. I knew I could. And I found the experience every bit as much of an accomplishment. For me, the solo wasn't so much a test as it was a graduation of sorts. A milestone for certain, but mile 20, and a chance to realize the importance of miles 1 through 19. As an added bonus, the flight to and from Colorado Springs provided a cool preview of the next 20 miles.

Final Stage Check (redux)

After three months of weather, scheduling, and maintenance conflicts, the day finally came for my final stage check. This was it. Pass thi...

-

After my last lesson and my somewhat dismal attempts at landing with a 7 knot crosswind, my instructor and I agreed that what I really nee...

-

A student pilot's first solo is arguably the most significant milestone in one's journey to becoming a pilot, or at least one that...

-

After three months of weather, scheduling, and maintenance conflicts, the day finally came for my final stage check. This was it. Pass thi...